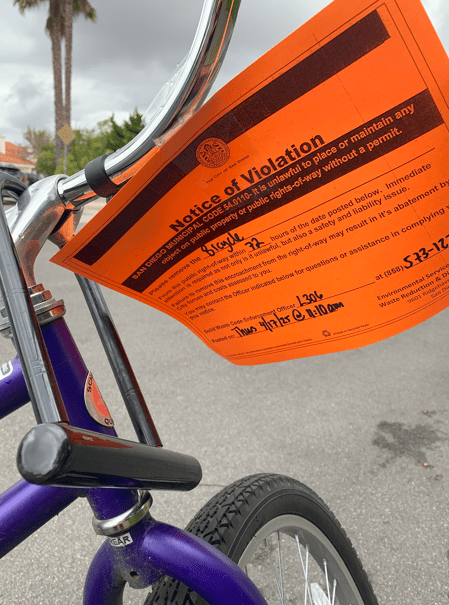

It has happened again, on the mean streets of San Diego, a bicycle in good condition sits abandoned in the street on its kickstand. Is it just sitting waiting for its owner to swoop in ride off into the sunset? No, because it was seated in the same spot for several days now. Was the owner just parking it there temporarily while they did their business in their home? No, because there were two bags from Vons with drinks in it that looked recently purchased. So, for the second time in a 12-month span, a brand-new bike has been left behind for multiple days, and it’s not just a case of abandoned bikes in a suburb of San Diego, it’s about the New World Economic Order.

Its tires are still full. The chain is oiled. The seat cushion is intact, if slightly weathered. There’s even a working bell—clear and chirpy, if you dare to press it. It’s a perfectly usable machine. And yet, there it sits. Days pass. Then weeks. Rain beads off its frame and runs down into puddles that reflect neon signs, cracked windows, and the creeping moss of time.

This isn’t just a bike. It’s a symbol. A quiet, two-wheeled eulogy for a city and a society grappling with urban decay, rising economic strain, and a throwaway culture that values convenience over connection. The bicycle didn’t break. We did.

The Bicycle as a Marker of Urban Decay

Cities are living organisms, and like all living things, they bear scars. The story of urban decay is written in boarded-up storefronts, flickering streetlights, and the hollow eyes of forgotten buildings. It’s not always sudden. Sometimes it sneaks in with every closed diner, every missed rent payment, every eviction notice tacked to a door.

An abandoned bike in good condition speaks to this decay. It’s a quiet casualty of a neighborhood in transition—or perhaps one in decline. In healthier urban centers, such a bike wouldn’t last a day before being repurposed, stolen, or lovingly claimed. Its continued presence suggests a lack of movement. Of passersby. Of hope.

In many cities, especially post-industrial ones, pockets of stagnation become permanent. The infrastructure remains, but the energy has bled out. The bike becomes part of the furniture. No one questions it anymore, like the scaffolding that never comes down or the graffiti that predates the last two mayors.

Yet, the bicycle is not just a victim of its environment—it’s also a mirror. It reflects the lost sense of utility that once defined urban life. There was a time when everything in a city had a purpose: the butcher, the corner store, the man who fixed watches in the basement of a dry cleaner. Now we walk past utility and see only clutter.

The Economics of Abandonment

Let’s be honest: this isn’t just about nostalgia or aesthetics. Money’s part of the story too. And not the fun kind. The rising-interest-rates-are-kicking-my-mortgage kind. In a world of low interest rates, credit flowed freely. People borrowed, bought, and upgraded. Cities gentrified. Buildings went up. Bikes got fancier. But as rates climb—and they have climbed, aggressively—so does the cost of everything: rent, food, credit cards, ambition.

For many, especially younger people and the working class, high interest rates mean the dream of ownership (of a home, of security, of the future) moves further out of reach. What once was a reasonable purchase becomes a questionable one. And what once might have been a necessity—like a good bicycle—is now just another item in a lineup of expenses to be postponed or ignored.

So what does this have to do with that bike? Maybe everything.

Maybe the owner couldn’t afford the rent anymore and left town. Maybe they defaulted on a car loan and had to liquidate everything quickly. Maybe they meant to come back and just… never did. Maybe the city, with its surging rents and frozen wages, simply became inhospitable to staying, let alone pedaling.

An abandoned bike in good condition is a symbol of economic dislocation—not just of one person, but of a system where things and people are constantly being priced out, left behind, or both.

A Ghost Made overseas

Let’s talk about manufacturing. Specifically, how something so well-made ended up on a curb like a forgotten soda can. This is the irony: we live in an era of mass production, where a staggering percentage of consumer goods—bikes included—are manufactured in China. Many of these items are made to be cheap, efficient, and replaceable. In short: disposable. The goal is not durability but churn.

This model fuels the economy and fills the shelves of big box stores. But it also breeds a deep disposability in our cultural DNA. Why repair when you can replace? Why value when you can discard? The bicycle, may have started as one of many in a shipping container, identical to thousands of others. And while this one happens to still be in working condition, its fate was never to be passed down to a grandchild. It was made for short-term use, for consumer novelty, not permanence.

Yet here it is—still intact. That alone is an act of rebellion. It defies the expectation of decay that its price point implies. But even that defiance couldn’t save it from being left behind. Not because it failed, but because we did. We’ve internalized the idea that when something is cheap, it’s also worthless. So we treat it that way. The tragedy is that sometimes, even the good ones—like this bike—get tossed in with the junk.

What We Leave Behind

At its core, the abandoned bike is about value. Or more specifically, our inability to recognize it. A working bicycle is a marvel of engineering and a symbol of freedom. It represents motion, sustainability, independence. In an age of climate crisis, where urban transportation is a key piece of the solution, the bike should be ascendant. Instead, it’s gathering dust.

Why?

Because the mechanisms of capitalism don’t just churn out things—they churn out habits. Habits of disconnection. Habits of detachment. We’re trained to move on quickly. To let go. To scroll, swipe, and replace.

Even our cities are subject to this churn. Entire neighborhoods get abandoned when they’re no longer profitable. Residents are displaced. Businesses close. But instead of treating these as systemic failures, we treat them like weather—unfortunate, but inevitable.

The bike is a footnote in that story. It’s not the headline. But it tells us everything we need to know. It tells us that someone once had plans. That someone once valued utility. That something once had purpose. And now? Now it’s just a relic. A reminder that in a world designed to make everything temporary, even the useful get left behind.

What Comes Next?

There are two ways to look at the abandoned bicycle. One is cynical. It’s another casualty of a broken system. A testament to decay, both economic and cultural. A metaphor with handlebars. But the other? The other is hopeful. Because unlike a shattered window or a condemned building, the bike is still good. Still rideable. Still capable of taking someone somewhere. If someone notices. That’s the trick, isn’t it? Noticing.

What if someone sees it and decides to take it home? What if someone fixes a brake pad, adds a basket, and starts riding it to work instead of driving? What if the bicycle finds a new owner—and a new purpose? That would be a small thing. But small things are how big things begin. Imagine if we started seeing our cities not as disposable but as repairable. If we started treating the people, places, and things around us as investments—not just costs. If we stopped chasing the new and started valuing the now.

Maybe the bike is the beginning of that mindset. Maybe it’s not a sign of what’s lost, but a symbol of what could be reclaimed.

A Final Note on Wheels and Worth

Cities don’t fall apart all at once. They unravel quietly. A broken light here. A missing tenant there. A good bike going to waste. And yet, cities also rebuild in quiet ways. One flower box. One painted mural. One person who stops to notice. The bicycle won’t shout. It won’t demand attention. But it has something to say, if we’re willing to listen. It tells us that we once built things to last. That motion is possible. That not everything abandoned is broken.

We are living through a strange era—one where we can access nearly anything with a tap of a screen, but increasingly find ourselves isolated, economically stressed, and environmentally imperiled. Our response has too often been to keep consuming, keep discarding, keep moving fast enough that we don’t have to look down.

But maybe we should. Look down. See the bike. See the story.

And maybe—just maybe—ride it.

Leave a comment